|

|

Home | High-End Audio Reviews | Audiophile Shows | Partner Mags | Hi-Fi / Music News |

|

|

|

30 Years Of Service To Music Lovers |

|

|

|

|

|

Jazz Memories:

Music of the Jazz Masters

Photographs from Herman Leonard

(Gravity Limited 2001: Distributed

by Innerhythmic/Caroline)

Article By Jim Merod

Louis Armstrong, NYC (1956)

This stunning compilation of legendary jazz photos and legendary jazz performances -- a boxed set that brings thirty-four photos by Herman Leonard together with two compact discs (and thirty one songs) -- marks a departure from the recent profusion of books that feature shots of jazz artists at work or behind the scenes.

First, there is maestro Leonard's unswerving visual beauty. The text begins with a cherubic casual portrait of Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. The two are presented, not as heavyweight be-bop masters on stage, but as happy men, relaxed in their most natural element: joking or clowning with one another for the sake of nothing but the sheer joy of it all. From that scene of delight, Leonard's camera work captures, one by one, the major artists whose music is featured on the two discs.

Disc one, track one gives us Louis Armstrong, in 1956, in the sparest possible setting -- playing "Dear Old Southland" with only Billy Kyle on piano (a reprise of Pops' 1930 recording with Buck Washington). The accompanying photo shows Armstrong back stage, trumpet nearby, handkerchief in hand, arm akimbo on his chair back, a pensive look of revelry across his tired face. It is a genuinely paradigmatic moment. The immortal Armstrong is all by himself, without pose or pretense, no audience to rouse his manic energies, no object of attention to draw him away from privacy and contemplation. We see, in a rare off-hand glimpse, the man himself -- somewhat sad, perhaps, but wholly at ease.

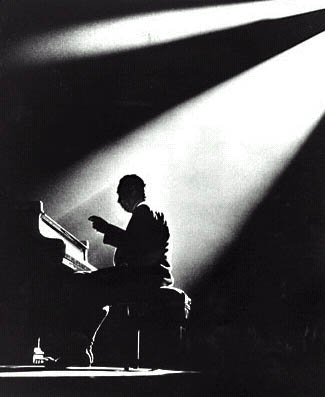

Duke Ellington, Paris (1958)

If there can be a perfect way to initiate a text such as this one, Leonard's photo and Armstrong's playing come together to approach perfection... for the objective of a multimedia compilation like Jazz Memories is clearly to trace the line of major artists that define the hundred-plus years of jazz history. That is a difficult undertaking. It has been achieved in this beautiful publication because the choice of subjects is right, the music assembled to exemplify them is genuinely representative... and Herman Leonard's photos are visually arresting and frequently magisterial.

A case in point will be found in the deeply probing shot of Art Tatum that accompanies the pianist's brilliant solo version of "Willow Weep for Me." We view Tatum's keyboard work laterally, as it were, late at night in 1950 at a Beverly Hills soiree. We see Tatum, in Leonard's moving portrait, however, from a position slightly above and to the left of the pianist -- eyes closed, hair trimmed, his lower lip thrust forward, chin cradled against his gorgeous folded hands. Light streaks Tatum's nose, smears the top of his forehead, and all but dances on the jutting lower lip. Despite the fact that the great pianist is wearing a nearly stark white jacket that catches the photographer's flooding accent light (as does the left background), those potential distractions do not intrude upon the frozen drama of the master's serene composure. Tatum's exotic face commands our attention. We are riveted by its sublime and almost unearthly calm. I cannot imagine a photo of Art Tartum that reveals the man's inner dignity more thoroughly than this one.

Highlights abound across this welcome collection of sounds and sightings. Open the text any place at all and find a visual nugget. Erroll Garner, leaning against the piano from his seat at the keyboard, is a study of mysterious self-enclosure. Gerry Mulligan, atop a stool in a recording studio, tugs gently at one stockinged foot, leg up, his horn upside down before him, a youthful smile of bemused contentment bathed in light. Turn the page and there is Cannonball Adderly, caught mid-guffaw, holding himself in a playful bear hug, a stub of cigarette shoved between two fingers just above the supine alto sax resting in his lap. You have to see the mirth that floods his face. It speaks precisely from the soulful, happy depth that defines the man's unrivaled playing.

I dwell with Leonard's graceful photos because they are uniquely beautiful. Each one carries a special awareness. Quite literally, a viewer of these shots can go over and over them without exhausting their pictorial nuances and their sub textual potential for allegorical or interpretive readings. An expressive example of just such inexhaustibility can be found at the volume's conclusion, in the innocent, shared moment of nicotine consumption that yokes Duke Ellington (perhaps speaking) with Billy Strayhorn (lighting a cigarette).

You can begin to unpack this fleeting moment by reference to the iconoclastic and utterly magnificent solo performance by Ellington that accompanies this photo: his inadvertently recorded version of Strayhorn's "Lotus Blossum" as his orchestra members headed off on a break during the session that created And His Mother Called Him Bill. That tribute album, conceived in dedication to the man Ellington called "Sweat Pea," stands by itself in the Ellington canon. This deeply moving meditation, Ellington playing alone, as if to himself, expresses a personal tenderness that is difficult to articulate or to catch in any medium. I regard that album and, in particular, Ellington's spontaneous performance luckily captured on tape, to be rare by any standard of aesthetic judgment.

Looking at these two men, sitting side by side in Leonard's quick shot of a seemingly insignificant moment, one finds an unassuming attitude of sympathetic companionship. The love that Ellington expresses for Strayhorn in the accompanying piano solo can be intuited already alive in the relaxation of their unexpressed partnership in the photo. Nothing is at stake there. Nothing could be more thoughtless or incidental than two men sitting together smoking. And yet the look on Ellington's face seems to solicit his friend and colleague. It is a look, on the older man's visage, that one might call plaintive or beseeching. The moment's quick and inauspicious fragility is rooted in personal history, deeply embedded with a casual sense of friendship. It is as if the two right arms captured in the photo -- Ellington's cocked beneath his chin, cigarette elegantly held just so, Strayhorn's parallel to Ellington's as he holds the lit match just beneath his chin -- express an unconscious unity of purpose... which, of course, no two arms (or hearts or minds) ever so thoroughly enacted before or since. There are other creative partners to celebrate, but what partnership achieved a higher degree of sustained brilliance than the one that joined Strayhorn and Ellington for three decades?

Something in the photo suggests the serendipitous and intoxicated artistic companionship these two men discovered, and mastered, in their daily work. As Ellington looks toward Strayhorn, looking over his shoulder as it were, the relationship of respect and surprise they surely enjoyed so often seems scripted in the unstated authority of master and pupil here dissolved in unpremeditated relaxation.

Dizzy Gillespie, Royal Roost, NYC (1948)

A word about the wonderful music selected for this volume. You can hardly ask for two discs so chock full of classic jazz, more than an hour and a half of music from Lester Young, Dinah Washington, Miles Davis, Sarah Vaughan, Bud Powell, Ella Fitzgerald, Sonny Rollins, Billie Holiday, Clifford Brown, Fats Navarro, Dexter Gordon, Thelonious Monk... and on and on. In virtually each instance, the tracks chosen are engagingly resonant with the photo text they accompany.

The departure from recent books of jazz photos is apparent not so much in the high production values of the music and the box set itself, although everything about this publication is first rate. Other books of jazz photos (by Carol Friedman and by William Claxton, for example) have been gloriously rendered. Perhaps what is so impressive about this box set is the simplicity and intelligence of its presentation. The explanatory texts that sit alongside each photo are informative and nicely rendered. The publication as a unit, an ensemble of many parts, is without mannerisms or self-conscious strivings for artistic impact. Instead, Jazz Memories gives us an enjoyable voyage across the music and the people who made an artistic heritage -- in sound and in the scope and variety of strong (and often captivating) personalities -- unlikely to be surpassed.

High-Performance Audio Reviews

High-Performance Audio Reviews