|

|

|

|

Smoke & Light:

The Jazz Photos Of Herman Leonard

At The Monterey

Jazz Festival, 2001

Words By Jim Merod

Photos by Herman Leonard

Louis Armstrong, NYC (1956)

Photographer extraordinaire Herman Leonard mounted an eye-opening display of jazz photos at the recent Monterey Jazz Festival (September 21 - 23) in the intimate confines of the Coffee House Gallery. For three days, Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday, Miles Davis, Sarah Vaughan and others again stood side by side, revealing momentary personal candor and permanent visual charm.

Leonard's work is among the most respected and widely admired bodies of photography in the world. It extends beyond jazz to embrace the realm of high art as well as the commercial and mundane. By any calculation, Leonard's jazz photography is remarkable. His two-dozen or so well-chosen images at Monterey showed why. Each image carries an almost painterly quality, combining the softness of tactile surfaces with the hard-edged clarity that only a superior camera can attain in the hands of a photographic master.

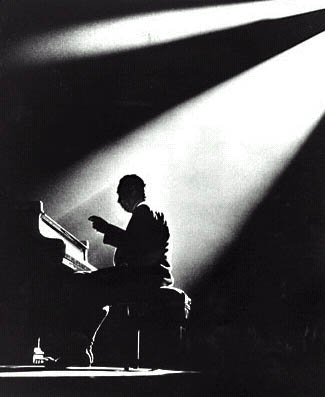

Duke Ellington, Paris (1958)

One of the arresting virtues of Leonard's work is the presentation of famous musicians in stark, sometimes brooding light. Such graphic treatment creates a lingering sense of drama, within each shot and among the group displayed, as if an unexpressed conversation between old musical friends has been suspended.

So many of Leonard's photos are stunning in their initial and lasting impact that it is difficult to choose one that represents the whole. Perhaps, a 1948 shot of Dexter Gordon comes close to being representational of the collection. When this image was captured in New York, Gordon was not the widely recognized jazz colossus who later starred in 'Round Midnight, a somewhat off-the-mark movie that allowed the slow-talking Gordon to create an on screen version of himself even as he carried out a cinematic "role" that improbably sought to combine saxophonist Lester Young with pianist Bud Powell.

In Leonard's powerful photo, the youthful Gordon, suave and seated, hat tilted back from his forehead, is shot from below as light pours down from the upper left corner. One of Leonard's signature practices is at work here. Light suffuses the scene with a seemingly intentional purpose -- as if an uncanny luminescent genie appeared at just the right moment in just the right place. There is another compositional element at work here, too. The river of light bathing Gordon's face and body is made dense -- visually palpable as an almost heavenly luminous body -- by the cascade of cigarette smoke from Gordon's exhaled breath.

Smoke and light: these own a magic of visual interaction that Herman Leonard exploits with purposeful artistic glee. Despite the reverence for the subjects of these photos, a viewer is mistaken to overlook the cheerful humor in them. Leonard's visual trick, one of many, is an invention carved from need. We should remember that the '50s and '60s offered world-class photo artists no help of the sort to be found in the digital world.

In short, the awkward photographic process that Leonard endured, hampered at each point by bulky cameras with manual focus, was turned to an asset. A somewhat plodding approach, dictated by necessity, became an artistic ally. Since it was crucial for Leonard to establish each shot by careful manipulation of the subject and the surrounding environment, Leonard created strongly-rendered fields of focused light for maximum drama. Smoke provided a way to catch and contour light's otherwise transparent presence.

The "representative" shot of Dexter Gordon employs the cumulative effect of smoke and light to hold the saxophonist in a church-like setting, at peace, hand resting on the horn cradled in his lap, ordinary life stilled a moment as the young man looks heavenward with self-satisfied innocence. Gordon becomes a secular variation of the pieta, a man lifted beyond himself into the heaven his art is about to express . . . or has just rendered. It is an early shot of a soon to be legendary musician that seems to capture a world apart, removed from the mundane entirely: the world of an eccentric but reflective musical dynamo.

One might note here that the power of Leonard's work is not something easily anticipated in the context of a large and boisterous jazz festival. After all, when five venues are simultaneously alive with music, as they often are at Monterey, the impact of still photographic images might be expected to wane somewhat under the burden of so much nearby sound.

That is not the case with Herman Leonard's art. Somehow it has established rules of its own. Although these jazz shots are highly crafted, at first glance the camera and its art are invisible. The musical reality, the human subject, takes precedent. These are not the same thing, but they work together (in concert, as it were) in Leonard's vision. It comes to something this obvious and direct. Jazz musicians provide convenient subject matter for a photographer with an eye for the casual or beatific moment. Jazz is the realm of the instantaneous and off-beat, life on the move. All of that -- the ragged and cheerful warmth of artists captured with unprepossessing dignity -- is rendered perfectly in these photos. On one hand, perhaps surprisingly, musicians are almost incidental to the drama of light and shadow that Leonard tailors to (and for) his vision. On the other hand, the many musicians who became his subjects both lend their charisma to his art and take from it a heightened personal stature. Once you see Louis Armstrong, Lena Horne, Count Basie, Dizzy Gillespie, Art Tatum, Ella Fitzgerald, Frank Sinatra, and others in the stark light of Herman Leonard's gaze, you are not apt to regard them as you did before.

Dizzy Gillespie, Royal Roost, NYC (1948)

On Sunday at Monterey, the festival's final day, everything at stake in Leonard's work was up for inspection in two public conversations. The nearly octogenarian world traveler lent himself to both with high spirits. In the first discussion, a breakfast gathering of professional jazz photographers held in the Artist's Bar near the Jimmy Lyons Stage, Leonard (who was the meeting's guest of honor) recounted some of the lessons he gathered during five decades of work. Later that day, he offered detailed commentary on a wide cross-section of his work to a respectful crowd of festival goers in the Night Club.

The theme that emerged in each forum was the importance of passion for the photographic artist. From an early moment in his photographic career, Leonard's enthusiasm about jazz has been unwavering. In the late '40s, as 52nd Street in New York became home base for the music's ferment, its many clubs (side by side) hosting jazz luminaries such as Charlie Parker, Coleman Hawkins, Dinah Washington, Dizzy Gillespie, Oscar Pettiford, and Art Tatum, the unstoppable Leonard went to work up and down the street. He drew upon passion for the music, but he drew upon a year's apprenticeship with the great photographic guru, Yousuf Karsh, as well. That experience brought Leonard into contact with Winston Churchill, Albert Einstein, Harry Truman, and other international figures. It taught him technical elements of his craft. It also taught him how to work with strong personalities.

Strong personalities, everywhere on display in the jazz photos mounted at Monterey, can be found in greater number throughout the large body of Leonard's art (which can be pursued immediately on his website: www.HermanLeonard.com). In Leonard's photos, strength of personality gives way to visual nuances and the calm of casual surprise. How could it be otherwise? One further quality stands out, too. Leonard's special way with light and shade, with form and the instant's fragile moment, evolves from his commitment to the person being captured. When the photographer talks (as he did at Monterey) about his long association with Miles Davis, he reveals a great deal about his own charm and about the charm that Miles -- as a man and as a subject -- held for him over the course of many years, as well.

One of the early shots of Davis on display at Monterey shows the twenty-three year old trumpeter, in performance, looking very much as we see him a decade later on the cover of his legendary album, Kind Of Blue (Columbia). Leonard did not take that photo but, in this one in 1949, Davis is shown from a close perspective, front and left. He appears to be the embodiment of personal poise and musical reserve. Later photos by Leonard reveal the ravages of time and substance abuse on Davis. They document, nevertheless, the trust that Davis had in Leonard's treatment of his image. One that holds particular appeal captures Davis in the process of sketching or drawing, a habit of visual artistic production that assumed considerable importance in Davis's final years.

Davis, of course, was not so gentle with many photographers. A well known photo of Davis by Lee Tanner catches the trumpeter, horn in hand, looking down at the stage-front camera, ready to utter a salty admonition. Other photographers (perhaps wary) sometimes seized a quick moment of Davis's musical intensity, or preoccupation, and thereby subverted potential confrontations. A striking 1989 shot of Davis, head down in the act of making music, rendered by Michael Oletta in haunted silver light, is an instance of the sort.

Leonard's visual world, in contrast, derives from the vantage of total photographic ease. It is at peace with a mood of elegance and simplicity that has almost disappeared from the world. Leonard and his subjects are partners. They share an unstated common bond. You feel complicity resonate between the camera's gaze and the subject's trust. In Leonard's photographic sphere only truth and goodness reign. Louis Armstrong sits before us with a wholly unselfconscious but regal bearing. In one shot (Paris, 1960), he is sober and introspective. Light explodes upon him, producing a vivid shadow of his head against the nearby wall. It becomes, perhaps, a covert image of the great musician's mysterious imagination. In another shot (New York, 1956), Louis is animated and singing, his ever present handkerchief ready to punctuate the verbal hijinx.

As we walk among photos that construct Herman Leonard's jazz Hall of Champions, we sense that we are looking into the depths of another cultural reality. Here is a very young George Shearing, newly arrived in New York from England, his perpetual smile cherubic and untroubled. There is Count Basie, at the piano in Newport, 1955, his right profile swathed in light. His fore finger points enigmatically across the piano, doubtless signaling to Frank Wess or Marshall Royal or Bill Hughes. Could he be asking the selfless Freddie Green to take a guitar solo? No matter, the ever-dapper Count is in the driver's seat. Only the music matters. All is well in the world.

If the shot of Dexter Gordon bathed in angelic light, the product of his own smoky breath, can be taken as an emblematic Leonard jazz photograph, one other shot holds its own representational magic, too. Frank Sinatra, his signature Jimmie Van Heusen hat cocked back, photographed from behind, becomes an image of hale farewell to the reality that these swarthy images propound. His left hand raised above, extended out before him, cigarette ever present, Sinatra punctuates his singing as only Sinatra could... with style and understated gestured drama.

The image of Sinatra -- saluting the song, the beat, the lyric's meaning, and his own insistent involvement in the choreography of sound and movement -- stands as the final gesture of an era forever gone, forever near as long as we have so much music left to hear and such images as these to fascinate us with their difference. That difference, crafted by a photographic maestro, Harman Leonard, compels us to wonder what he felt, what his subjects knew, what ease and grace and authority they shared those many moments when stage lights dimmed and the awkward, unassuming camera found music's inner meaning in smoke-sculpted light and the casual ease of so many willing, brilliant subjects.

Website: www.hermanleonard.com

All photos copyright © 2000

Herman Leonard Photography, L.L.C.

Used with permission